There was fascinating new report out a few days ago on Faith and Belief in New Zealand. Produced by McCrindle, an Australian research firm, under commission from the local Wilberforce Foundation, it is a fascinating collection of material, of the sort not often seen in New Zealand. The report itself states the purpose

The 2018 Faith and Belief in New Zealand report, commissioned by Wilberforce Foundation, explores attitudes towards religion, spirituality and Christianity in New Zealand. The purpose of this research is to investigate faith and belief blockers among Kiwis and to understand perceptions, opinions and attitudes towards Jesus, the Church and Christianity.

and the approach

This research employed qualitative and quantitative methods to explore Kiwi perceptions and attitudes towards Christianity, the Church and Jesus. These methods included a nationally representative survey of Kiwis, a series of focus groups with non-Christians and analysis of Census data from Statistics New Zealand.

It draws from similar work undertaken in Australia.

I’m mostly interested in writing about what is in the survey, and what we might take from it. Nonetheless, it is worth noting some of the limitations (most due to the small size of sample, in turn presumably due to cost considerations). There is, for example, nothing of an ethnic breakdown – increasingly common in New Zealand polling and research these days – and also, within the Christian subsample, no denominational breakdown, not even at a relatively high level (eg Catholic vs Protestant, evangelical vs liberal and the like). The survey seems to have identified Protestant vs Catholic/Orthodox, but the sample sizes were probably too small to do more with that information. By contrast, in Pew research in the US these breakdowns often produce a lot of interesting results. If Wilberforce is ever looking to do more work in this area, I hope they think about a large sample, and more disaggregation.

Here is the first breakdown

That seems not inconsistent with the most recent published Census results (for questions posed differently), bearing in mind that the Christian share is likely to be lower again in this year’s Census. Around a third of New Zealanders, in this sample, “currently practice or identify with Christianity. That seems a slightly more demanding question than the Census question “what is your religion?” Some who no longer practice or identify as Christian but were born or raised in a churchgoing family, or even just baptised as an infant decades ago, may be happy enough to write down “Anglican” or Presbyterian” or whatever. This isn’t a Christian country, even if the number identifying as Christian still far exceed those identifying with any other organised religion.

And of that third who still identify as Christian, only around half state that they attend church even monthly. A more common metric is to look at those who identify as attending weekly (or more frequently) – a later question suggests 12-13 per cent of survey respondents are weekly attenders. Perhaps it just comes from living in very secular Wellington – although of the three big cities, the survey suggests Auckland is least Christian – but I don’t believe that 17 per cent of the population is in church with reasonable frequency (there was probably a bias for respondents having identified with Christianity to overstate their attendance frequency) or that 12-13 per cent are in church weekly. From observation of local churches, in my own suburb 5-8 per cent would seem more plausible.

As a marker of the problem – the increased secularisation of New Zealand – there is this age breakdown

Some of that will be a decline of nominalism, but that is (very) unlikely to be the bulk of the story. In a subsequent question, a materially smaller share of the young describe themselves as actively involved than among older respondents.

The decline is captured in this chart.

A small number of converts (to any religion in this case), and a huge proportion of respondents who were raised in a “religious household” (however loosely respondents themselves took that as meaning) but have since walked away. And, of course, the large (and presumably increasing) share of those non-religious from the start.

This is a sobering chart.

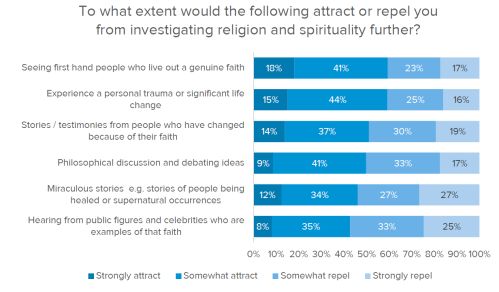

Remarkably, 40 per cent of people reckon that even seeing first hand people living out a genuine faith would make no difference. If it works for you, that’s fine, but that has no implications for me, presumably. No sense of the possibility of absolute truth? A reminder, I suppose, that conversion isn’t some abstract thing, but a response to ground prepared by the Holy Spirit.

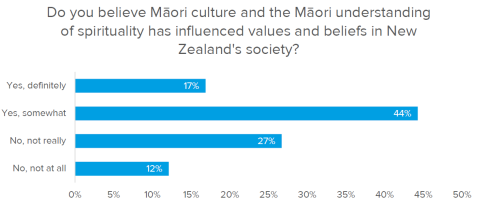

What of the influence of Maori culture in New Zealand?

I’m not sure what to make of this question. I’d probably have answered “no”, but more accurately the answer would be “it depends”. In vast swathes of New Zealand society (European as well as Asian immigrants) I suspect the answer is none at all – I detect no influence in my own values and beliefs, which seem very similar to those of British evangelicals – but there are parts of society where things Maori have undoubtedly made inroads. In a follow-up questions, the key aspects highlighted were acknowledgement of sacred places (like church, or a war memorial, or a cemetery?), importance of extended famility, and respect for elders. In general, I struggle to think of evidence suggesting those are stronger here than in the societies from which most of us originally came.

Somewhat to my surprise, respondents still seem to support the (voluntary) religious instruction offered in some state schools.

And what issue block or engage New Zealanders around the Christian faith?

It was intriguingly phrased – I missed the question “a recognition of my own sinfulness and the reconciliation with God offered in Christ Jesus”. But, in today’s climate, I wasn’t surprised by the top-ranking issues. For millenia – two even in the Christian era – the church has taught, along with natural law, that homosexual practice is sinful (not more sinful than many other things, but sinful nonetheless). Judaism and Islam took the same view. And now 66 per cent of New Zealanders list that teaching – often pretty attenuated these days – as a block to “interest” in Christianity. It is, they report, less of a block for non-Christian who are warm to Christianity than to those completely cold, but even for that group it is a significant stumbling block. Which isn’t grounds to abandon or change the teaching: Paul, after all, could write of the cross itself as foolishness, or a stumbling block, to those who don’t believe. But it is sobering nonetheless – probably a predictor that the church will keep watering down its teaching, but also a reminder of the uphill task of calling a nation like ours back to God.

As perhaps are some of these (even recognising that sin will always be with us, within the church as well as without).

How have we failed to convey (to live?) the fundamental belief that all (of us) have sinned and fallen very far short of God’s glory, that a growth in a walk with Christ should only make us more aware of our own sinfulness and need for God’s grace?

It is interesting to see what people do value in the church.

There is nothing wrong with any of these things, of course, but the church is supposed to be more than a badged welfare provider. I guess the option of “it helps me sustain my walk with Christ, and faltering witness to him” wasn’t offered even to Christian respondents.

This is probably the closest (but also where a lack of disaggregated data is frustrating)

There are a few surprising, mildly encouraging, results. A quite surprisingly large proportion of respondents claim to know about Jesus’ life

And 45 per cent regard Jesus’ life as important to them personally. I struggle to know what that means, when only 33 per cent claim to identify with Christianity, but results are what they are. And there are some specifics:

Perhaps some of those are pretty attentuated descriptions: “love” seems to mean everything (the user wants it to mean at the time) and nothing. But 30 per cent – far more than go to church regularly – mention grace and salvation. Prompts – in the survey – probably help, but it is interesting nonetheless.

I’m a data junkie, so I really enjoy working my way through survey results like this. I don’t come away hopeful – at least in our own strength – and keep thinking of other questions I wished they’d asked (eg about religious liberty, outside the four walls of the church). I’m also wondering what the greatest stumbling block respondents to similar surveys might have identified in other times and places. I suspect the unchanging teaching on homosexuality wasn’t the big obstacle in early Britain or among 19th century Maori, or Nigerians or Ugandans of 100 years ago. Whatever it was, by God’s grace, those obstacles were overcome. I wonder how people would have responded here even 50 years ago? Whatever that obstacle was, it presumably wasn’t overcome.

Of course, even the people of Israel went through very dark times – of slavery, exile, foreign rule, and a widespread abandonment of Yahweh, who yet never abandoned them. God doesn’t give up on his purpose, calling all men and women to him. And yet in individual places – countries, regions – the light of the gospel has been snuffed out almost completely (see modern Turkey). Our prayer and passion – and I as much as anyone need this prompt – must be to work and to pray, to witness and to teach, to form our own people, our own children, in the way of Christ, to be ready for the fresh wind of God’s Holy Spirit to blow one day through this land.

Some great analysis here – I started reading the report but even though I’m a data junkie myself got a bit bored with its format. Your discussion and analysis was much more interesting.

Talking of data, the religion results from this years Census will be of interest, especially the denominational aspect. I work for Stats (on the economic side), but was a bit surprised with the wording change on the question. I did wonder what the cognitive testing results were on it, but having only one box (religion only) instead of two ( religion + denomination) at least on the online version will change the result quite a bit. I know for my family at home we would have all put Christian and Anglican last time, but this time only I put “Christian – Anglican” (and I had to type that) – the rest all put “Christian”.

Anglican is not a religion (even though it was listed in the drop-down) – and most church-going people I know would answer Christian instead of any denomination be it Anglican, Methodist, Baptist, Reformed or whatever. Catholics might be an exception to that and may be more likely to write Catholic – we shall see I guess.

I know that the claassiifcation is hierachical, so if you put Anglican then it you will go under Christian, but that is not what the question asked.

LikeLike

Thanks.

I hadn’t noticed the change in the census question (I use that question to indulge my mild anarchist/privacy tendencies and refuse to state).

LikeLike

Michael I totally understand the question about the influence of Māori culture. Culture is often hard to separate from religion, which is why many Māori, upon converting, eschew Māori custom.

I work for a government organisation that is pushing all staff to be more comfortable with Tikanga Māori. Part of this involves all staff knowing and being able to recite their mihi, and to begin meetings with a (either secular or Māori spirituality) karakia. The concept of mihi, and being able to recite your genealogy is more than just knowing who your ancestors were, it is integral to the shamanistic Māori religion as are hongi (the sharing of breath has spiritual significance). Reciting your mihi is another way of reminding the guardian spirits of your enemy/stranger that you are calling on your own ancestors’ spirits to defend you.

I refuse to engage in these activities as I believe the workplace is best left secular, but management disagree. (I have heard of colleagues who have been rebuked by their manager for not participating.) So the widespread acceptance in New Zealand of certain “cultural” practices are actually the widespread engagement with, and acceptance of Māori spirituality, whether they know it or not.

I suspect this is why the question was included (I also suspect the Wilberforce foundation is strongly Arminian in outlook). Thanks for bringing it to my attention.

LikeLike

Interesting point (and another to add to a list of why I’m glad no longer to work for govt organisations). Altho examples like your mihi one, or Morning Report and its heavyhanded use of Maori, probably still don’t show that Maori culture has influenced values or beliefs generally – it is more like a tokenistic overlay by some public sector agencies, rather than something NZers generally have embraced.

LikeLike

My goodness the refusal to acknowledge or accept the place of Māori spirituality culture or language as normal in this post and the comments are more depressing than the stats. I hope you are proud of your refusal to engage in Mâori discourse of any kind. Heaven forfend you should ever learn something that doesn’t spring from the pages of Elsdon Best. I was going to share this post to a Māori Christian group. What an insult that would be.

LikeLike

I don’t think I expressed a particular view. My interest was mainly in understanding the survey, including reflecting how I might myself have answered those specific questions. I remain a bit sceptical that Maori culture and spirituality have materially influenced non-Maori NZ values and beliefs, but ultimately it is an empirical question. At the level of introspection (ie simply one data point), I find little evidence that my own values and beliefs, as a native NZers, are any different than those of evangelicals in, say, the UK or Australia.

LikeLike